Collaborating with the Creative Spirit, Still / Galen Garwood

Part I

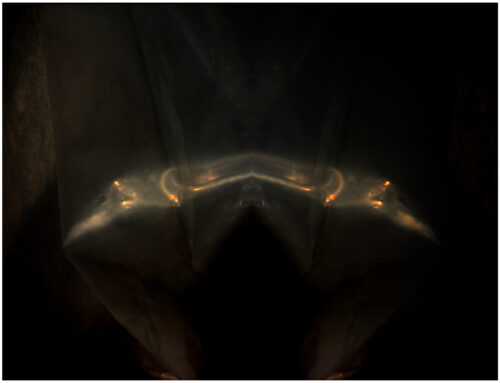

In 1983, I completed a series of small paintings on Plexiglas in a reverse, reductive process. These were dark, figurative tableaus coming wholly from whatever was feeding my imagination; I had no specific narrative in mind. I was mostly experimenting with ‘process,’ something new I’d never tried, but still, relying on a sense of shape and tonal relationships, of implied textures and setting the male figure squarely in the stories. Before I exhibited the paintings at Foster-White Gallery in Seattle, I showed them in a small space next to the Imprint Bookstore in Port Townsend, Washington, where I’d just moved. That afternoon, Sam Hamill, poet, and editor of Copper Canyon Press stopped by and spent an hour perusing the works. As I’ve written previously in my autobiography, Sell The Monkey, this event became the beginning of PASSPORT, a series of response poems by Sam.

One of the images I created appears to be a young boy, standing in front of and facing a wall, both arms raised in which is cradled the thin line of an inscribed circle, something symbolic perhaps of either giving or receiving. Unidentifiable objects move left and right out of the bottom picture plane. I do remember thinking at the time the larger shadowy form at the bottom felt like ‘animal,’ sheep-like, moving off to the right, only its fluffy back-end remaining in the picture.

Several months later, I stopped by the Imprint Bookstore to look for a book to read during my next period of isolation at Galax, my mountain retreat in Eastern Washington. My eye went directly to a newly published book on the top shelf entitled The Gift, by Lewis Hyde. I’d never heard of Lewis Hyde nor the book, but the title intrigued me. It was a good choice. Reading it became an all-consuming, enthralling experience. The Gift, a book of which Margaret Atwood wrote, “a masterpiece and a ‘classic study of gift-giving and its relationship to art,’” is still changing people’s perspective on why we make art.

Ending his book, Lewis adds one last story. He writes about the poet, Pablo Neruda, adding Neruda’s own account of when he was a young boy playing in his backyard at his home in Chile. A tall fence separated his family property from the neighbor’s.

In the wooden fence was a hole. Neruda writes: “I looked through the hole and saw a landscape like that behind our house, uncared for and wild. I moved back a few steps because I sensed vaguely that something was about to happen. All of sudden a hand appeared—a tiny hand of a boy about my own age. By the time I came close again, the hand was gone, and in its place was a marvelous white toy sheep. I had never seen such a wonderful sheep. I looked back through the hole, but the boy had disappeared. I went in to the house and brought out a treasure of my own: a pine cone, opened, full of odor and resin, which I adored. I set it down in the same spot and went off with the sheep.”

Neruda recounts that eventually, growing older, he lost the toy sheep, but never lost the memory of that unspoken gift exchange. He writes: “maybe it was nothing more but a game two boys played who didn’t know each other and wanted to pass to the other some good things of life. Yet maybe this small and mysterious exchange of gifts remained inside also, deep and indestructible, giving my poetry light.”

Something took root and bloomed in all the reasons he wrote poetry, his purpose for making art.

When I finished reading this part of Hyde’s remarkable book, the image I’d recently painted rose up: the boy in front of the fence with his arms raised, holding the circle, the sheep-like form, the luminous black and white of the painting, the sense of time and space—all of it came rushing into the foreground of my thoughts. I shuddered. It felt like a Deja Vecu, a feeling of somehow having lived through another’s life…but not precisely.

I was so taken aback by these connective associations, on the following day, mentioning my experience to a friend, I expressed an urgency to write Lewis Hyde, who lived on the East Coast. I felt I needed to share these strange coincidences. Pat smiled and said, “Not necessary. Lewis will be here in two weeks. He’s been invited as ‘writer-in-residence’ at Centrum, right here in Port Townsend. I’m sure you’ll meet him.” I looked at her, blinked a few times, and began to wonder how many other colors could thread themselves into this mysteriously unfolding tapestry. There turned out to be more. The poem that Sam wrote for this particular painting in 1983 is titled ‘Aún,’ which means ‘still’ or ‘yet’ in Spanish, and is about Pablo Neruda. Hyde’s book, The Gift was published in 1983, the year I moved to Port Townsend.

About seven years earlier, the Poet and Neruda translator, William O’Daly began translating his first Neruda book entitled Still Another Day (In Spanish, Aún) and it was published by Copper Canyon press in 1984. That summer, I did, in fact, meet Lewis Hyde, and we became friends. Sam Hamill and I developed a long, fruitful friendship, and through Sam, I met Bill O’Daly, whom I’ve held in strong brotherhood and constant communication, sharing numerous collaborations over the last thirty-five years.

Is there something more than mere coincidence involved in all of this? I wonder.

I’m aware that science shudders at the possibility of anything remotely prophetic and I have more than a few friends who, while they might respect my creative imagination, would discretely shuffle me into the back room of ‘New Ageism’ for suggesting any of this is more than serendipitous circumstance. That’s fine. Still, I distinguish between truth, which is virtually inaccessible other than through subjective belief, so steeped in mystery it is, and science, which is but a consensual agreement on what we call facts based on the evidence we’ve gathered within the framework of what we call reality. Said another way:

Science and truth are not necessarily the same and both continue to evolve. Mystery, however, is always steadfastly in front of us.

As Hyde explains, the root of our English word ‘mystery’ is a Greek verb, meuin, meaning to close one’s mouth. Dictionaries have long defined the connection to mean the initiates of ancient mysteries were sworn to silence, but, as he believes, it might also imply that while mysteries can be witnessed, revealed, or talked about, they cannot be explained. I agree.

But, to me, the main reason I’m writing about an event or experience that felt pre-ordained reels back to why I believe art matters. In The Gift, Lewis writes, “The main assumption of the book is that certain spheres of life, which we care about, are not well organized by the marketplace. That includes artistic practice, which is what the book is mostly about, but also pure science, spiritual life, healing, and teaching…This book is about the alternative economy of artistic practice. For most artists, the actual working life of art does not fit well into a market economy, and this book explains why and builds out on the alternative, which is to imagine the commerce of art to be well described by gift exchange.”

Amen, Brother. Amen.

After half a century, as I move into the next and perhaps deepest journey yet, I’ve been envisioning ways through which I can enter a period of focused creativity in a kind of cradled solitude, wrestling only with questions and demands of artmaking itself. The concepts of both patronage and investment have threaded their way into a blueprint of possibility. These seem divergent activities, external to the artist’s search. But are they?

In my next posting, I’ll offer Part II of my ideas, currently squiggles in the blueprint, yet taking shape.

Interestingly, when I was back in the US on the book tour, I participated in a fascinating event held in Seattle, a new energy movement entitled ‘Salon for Good’ a resurrection-idea moving from the mind of writer, Nirupa Umapathy. “The premise,” she offers, “is to have a deeper, non-judgmental conversation on what undergirds an artist’s journey, their practice and the critical role of community and patronage in supporting such practice…unlocking the power of arts, architecture and ecology for personal transformation and community revitalization.”

This idea, coming out of the French Enlightenment of the 18th Century, from the salons of Paris, from those remarkable women, was transformational in nurturing self-education and patronage, through a sense of community and communal voice, i.e. understanding the ‘gift-exchange.’ Hyde writes in The Gift: “The creative spirit moves in a body or ego larger than that of any single person. Works of art are drawn from, and their bestowal nourishes, those parts of our being that are not entirely personal, parts that derive from nature, from the group, and the race, from history, and tradition, and from the spiritual world.”

Seattle, 2018, JW Architects. Nirupa Umapathy, Galen Garwood, and Liz Tran reflecting in the imagination of Liz Tran’s installation, reflected in mirrored discourse about art, and community, and sharing ‘story.’

OVER AT MARROWSTONE PRESS

Next month, on November 15th, Marrowtone Press launches a remarkable new book of poetry

YOU WAIT FOR ME WHERE MOUNTAIN PEAKS ARE WHITE AS YOUR HAIR

Peter Weltner has published six books of fiction, including THE RISK OF HIS MUSIC, HOW THE BODY PRAYS, and, in 2017, THE RETURN OF WHAT’S BEEN LOST. He has published five poetry chapbooks, the most recent WATER’S EYE, and five previous full length collections of poetry, among them TO THE FINAL CINDER, STONE ALTARS, and, in collaboration with the artist Galen Garwood, LATE SUMMER STORM IN EARLY WINTER. He and his husband live in San Francisco’s outerlands by the ocean

In early 2019, look for a new book by

The Safety of Edges poetry

![]()

And, yes, Sell the Monkey, is now available in both paperback and Kindle

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.