INTERVIEW WITH STEPHEN YATES, August, 2017

Very soon after I’d moved from Seattle, Washington to the lovely Victorian seaport town of Port Townsend, Washington, I had the honor of adjudicating the annual art exhibition, featuring various and accomplished artists from the area. One in particular—in fact, the one I chose as First Place—was a stunning painting by Northwest artist, Stephen Yates. During the seventeen years I lived in Port Townsend, Stephen and I got to know each other quite well, participating in a number of cultural events in the area. It’s been fascinating and rewarding to watch his evolution into a mature painter, one who keeps making art with the same passion he did as a younger man. I wanted to get his current perspective on art and why it matters, so I asked him to sit down with me for an interview. Galen Garwood

GG: I’ve been noticing that we’ve both been stacking the canvases for quite a while. When did you first realize or decide that you wanted to make art, to be a painter? At what age? And is there someone who helped kindle the fire?

SY: I knew from a very young age that I would be an artist. I remember when I was about four, a Sunday School teacher encouraged my coloring and my feelings of being so “into” the process – blending crayon colors and mark-making enthralled me. I always made art and was complimented on it, so I was stimulated instead of squelched like many children. I often won awards or recognition for the things I created and didn’t really doubt that artmaking was my path. My father was a talented seascape and landscape painter, and we had his art all over the house. My mother would have been an interior designer or architect if she hadn’t married and had to help raise our family; but her emphasis on very particular interior furnishings was also a little-acknowledged influence on me. I was raised in a small city, Pocatello, Idaho, and then moved at 13 to Boise, but both had little access to art other than family and teachers. I always felt a little starved for more access to art and artists. I had a number of talented working artists as teachers, and they were a great help to me in sorting out my interests.

Looking In A Small Pool 54″ x 80″ 1987 Stephen Yates

GG: From your works of the early 1980s until the most recent paintings, you’ve focused a great deal on the spirituality of water, both externally, as in some of your earlier abstracted seascapes, and internally, as seen in these more recent works, as if one is inside a universe of molecular explosions—color, textures, patterns, and movement. Was it when you moved to the Olympic Peninsula, with water and reflections of light so abundant to the eye everywhere, that your fascination took hold with the sea?

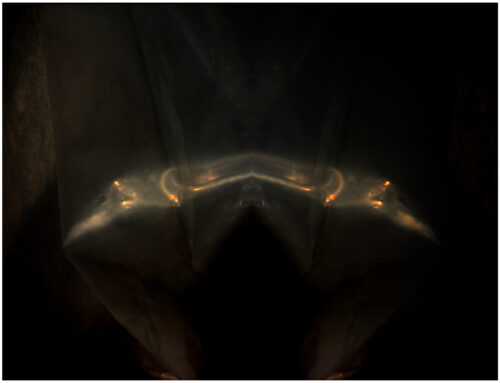

SY: I have always had an affinity with water even though I was raised in Idaho where there wasn’t much water except in swimming pools, rivers, and reservoirs. I spent a lot of time as a child in those places swimming in the summers (as a Leo on the cusp of Cancer, I am tuned to sunny weather and connections to water.) Later I visited the oceans in Oregon, Washington, California, Florida, Hawaii and in college, the Mediterranean Sea and the coasts of England, France, and Spain. I went to graduate school in Lawrence, Kansas and there was little water to be seen except in swimming pools, and I found I had a craving for water scenery and painted a lot of water imagery there, usually referencing earlier memories. I felt connected to the water in all of the places I visited and many earlier paintings reference those experiences quite directly, like Sete’ which was a potent memory of swimming in the warm turquoise sea at Sete’, France in my 20’s. When we moved to the Olympic Peninsula, we lived on the beach at Oak Bay on Marrowstone Island and the things that compelled me the most were the nightly sunsets, mysterious imagery under the water and the reflected light. In recent years I have often painted water and now like it when the imagery can be read in various ways – forms moving through ‘atmosphere’ that could be underwater or outer space or a view under a microscope.

Golden Strata, acrylic on canvas 48″ x 48″, 2014, by Stephen Yates

GG: I suspect one of the most difficult things for an artist is to know or feel or to simply decide when a painting is finished. Do you have a mental blueprint, or a philosophy, to guide you, when you finally say, “OK. It’s done,” and you walk away with absolute conviction? Or do doubts linger?

SY: Knowing when to stop is hard to explain. My work for some time has been mostly intuitive with no real blueprint to follow. I start making marks or putting down or removing paint and add more in “passes” or layers, building to a completion. Part of the process I have come to rely on is to use paints fluidly on a flat surface so that they will drift and coalesce as they dry, usually after I leave the studio. This letting go of controlling every brush mark and instead letting natural forces make some of the decision-making is very interesting to me. Sometimes this results in amazing things and other times the paint all drifts into a mud puddle. After that stage I go back into the piece with more marks or layers of paint. It almost feels like adjusting the lens looking through a camera until it is “in focus,” or it “snaps” into place or everything “clicks.”

Sometimes the painting will become clearly focused in a short period of time and will feel complete and I’ll know it is time to stop, or at least let it wait for a while and come back to view it again. Other times the process creates disappointing results and I either continue to add to it until it resolves or I put it aside. I always feel a little defeated when the piece doesn’t come together, so my inclination is to keep after it until I’m satisfied with it. I’ve found over the years that a piece I felt was good at one point doesn’t hold up over time, so I may go back and paint over it later, sometimes in a few months and other times a few years later. I’ve also found I am happiest with work when I can leave it a little short of complete so that it has some breathing room left, some possibilities not totally resolved, some mysteries unsolved. It is certainly a curious process!

Swoop, acrylic and charcoal on panel, 36″ x 84,” 2004 by Stephen Yates

GG: I completely agree, Stephen. The painting must be able to anticipate itself. And the hallmark of a caring artist is one who allows that, one who lets the painting decide when it’s time to be let loose into the world. I think all too often that ‘state,’ if you will, is lost when artists become too incurious and begin to copy themselves. One of the impressive qualities of your gift is that you seem to always be in search of, to experiment, to accept the possibilities of different visual languages. And, in a way, it is this kind of uncertainty and curiosity, that keeps art vital.

That is interesting because I have said on occasion that I wish I could figure out why some artworks are successful and others aren’t even though I am using the same approach and techniques. If I could accurately formulize it, I might generate tons of similar work, but that is rarely the case.

GG: Of that, for you personally, why? Why do you make a painting? Why make art? And for the rest of us, why does art matter? How do you perceive yourself in the grand linkage of it all?

The questions of why art making matters are intriguing and ones I have thought about often. Personally, it is a compulsion of sorts. If I didn’t feel compelled to do it, I would have abandoned it long ago when struggling to make money and raise a family seemed to be in conflict with taking the time to make and promote my art. I have been committed to the world of aesthetics since childhood. Ideas about art and images have always fueled my life’s interests. I like to look at art, I like to make art, I like to engage with art settings like galleries and museums, and I filter most of my experiences through the sieve of visual responses.

Who knows how or when those desires get created in a person?

I remember being thrilled with visual things even as a young child. It was an inherent part of my nature, and I was fortunate to be raised to appreciate and nurture it. Although I had excellent instructors in school, I always felt I was in a way self-trained and educated in that I had a craving to learn about art, art makers, art history, and the current art world and found ways to discover what they were about.

Over time I have come to realize that the question of why art matters is both individual and societal. There is something to the idea that we all start with positive, pleasurable aesthetic responses and our culture tends to dampen them or channel them in particular ways that make most people feel early on that the arts have less value in their lives than sciences, business or generating profits. Maybe that is for the best because it filters out the ones who really want to be involved, but it also does a great disservice to everyone who doesn’t receive the tools to be involved in art dialogues whether as an artist or a viewer-participant. I am an advocate of education that at least exposes people to art and art history. A liberal arts education helps create a society where more people can be conversant in the ideas that make up our culture. My introductory courses in high school and college were some of the most meaningful, thrilling and useful things I ever learned – Intro to Philosophy, Intro to Sociology, Intro to Ecology, Intro to Music, Intro to Literature, Intro to Drama, Intro to Music, Intro to Art History. Teaching our cultural history should be at the core of our educational requirements so that most people could appreciate our achievements and progress, not just a small group. Without understanding the arts are seen as elitist instead of elemental.

I like this quote: “The artist is the advance explorer of the societal consciousness. As such, many times his first reports are disbelieved.” David Mamet

My guess is about 30-40% of a community are interested in any of “the arts” with about 15-20% interested in visual art, and maybe 5% are interested in contemporary abstract art, so the audience is small for the things that I like and connect with. I try to create and present art that is accessible while remaining an abstractionist and often feel like a voice in the wilderness! I do feel comfortably linked to the arts and other artists. Choosing to live in a small rather isolated town has meant sacrificing exposure and opportunities in the “art world,” and I would make different choices if I were doing it again, but I enjoy being involved in the local art community and supporting art where I am. I do feel like a link in the ongoing art maker’s saga.

Navigator’s Strategy, 72″ x 120″ 2017, by Stephen Yates

GG: Well said, my friend; I agree. So what’s next on your creative calendar? New projects? Any Upcoming exhibitions? Is there a new series of images seeding itself in your mind?

SY: This summer is very different from last year when I was busy creating new work for an exhibit at Northwind Arts Center here in Port Townsend. Now I don’t have any deadlines and am just enjoying creating new work. A new painting “Navigations – Hawk Maze” will be in a group juried exhibit next month “Expressions Northwest (the 19th Annual.) I am planning a solo exhibit at a small gallery here in Port Townsend in September and I am looking for new possibilities to exhibit. I have started two new series, one photographic and another dealing with patterns, so there are always reasons to go to the studio.

Portrait of the artist by Galen Garwood, 2015

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.