Greetings Everyone,

I’d like to wish all of you an endearing Valentine’s Day, in any way you might wish to celebrate the holiday. In these times, Valentine’s Day is generally accepted as a vow of love between two people, though its history is steeped in mystery and variations of origin. Most early references are associated with events of martyrdom and the courage to follow moral convictions of the heart; this embodies and sustains goodness, and what is right. That’s love.

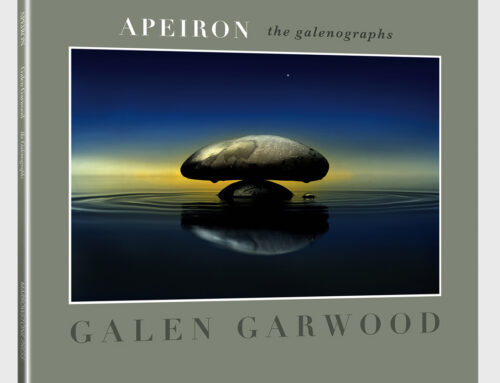

TETHERED ORBITS

Donald Isle Foster and Jan Thomson, Seattle, ca. 1999, photograph by Terry Arnett

When I first met Don Foster in 1972, he’d recently purchased the Richard White Gallery in Seattle’s Pioneer Square from Dick White. Very soon thereafter, I met Jan Thomson, who worked week-ends at the Gallery. Both, in their own various ways, became legendary in the structural rhythm of Pacific Northwest Arts. My first exhibition at Foster/White was in the autumn of 1973. Though Seattle is quite different today than it was then, many of my fellow artists exhibiting at the gallery and legions of new ones remain vibrant contributors to the vital spirit of Northwest Arts.

FEATURED ARTIST:

On This Day, Valentine’s Day, in the rich exhuberance of red hearts and love, women, entwining elephants, captivating birds, and the boy in the boat, I do so honor my friend and mentor, the late Lennie kesl.

UPCOMING and UPDATES

In the next issue of ‘The Journal,’ news about the Elephant Heart Project. Stay tuned! Coming soon!

Galen’s unabridged definition for ELEPHANT HEART: Igniting creative expressions through poetry, prose, and visual imagery, nurturing the critical synchronicity of life and life’s habitat, our home, planet Earth—a communion of sacred reciprocity.

![]()

painting of elephants by Thai students from the school of hearing imparied, Chiangmai, 2002

Also, Chang Lek and I are pleased to announce the upcoming Elephants and Art Winter Tour in Northern Thailand. Be sure and check the March issue.

![]()

For an update on STRAIT ART, Jake Seniuk’s remarkable book published by Marrowstone Press.

Coming in April: a featured interview with the remarkable American artist

LIZ TRAN

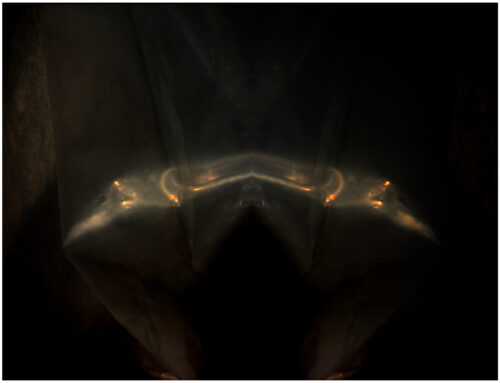

Oylosedentos, Galen Garwood, galenograph, 2020

SOMEDAY, for kados

There is, of course, the hue, I said

and of the hue,

should it be warm? Red?

Burnt Sienna?

It is blood, he cautioned,

sun and earth.

But you’ll also need

what is cool—green to blue to black,

like strata of the sea.

We were standing near the edge of a spent field

of grain that fell to the sun and a raking mistral.

I brought only questions, I said, as he turned to his work

with a stony silence, chewing on the stem of cold, blue pipe,

facing the wind, the fierce slapping of canvas, waiting

for imagination’s raw nerve to let go a vision.

There is intensity, I said, and purity.

How deep the shade? How bright?

how much white? Should I

consider the opacity

and the amount of light let through?

Should it recede or dominate?

Remember, he said, within the color there is the passage.

You might expect it to end all at once,

but it doesn’t. It often wants to modulate

from cold to hot,

hot to cold.

Yes, but will the hue be held by line? And the line,

will it be long or short? Thick or thin? How it should be broken?

Or should it? Should it be continuous, holding

everything in?

Should it be dark or light? What value

and should it shift?

What weight?

Check for sincerity, he barked.

Lines can lie. Remember

there are timid ones, as well,

with low, slow curves that drift

unattached. Consider this: every line

has a beginning and an end.

Where does it start? Where

and far will you take it?

It might only be implied.

I continued.

What about chiaroscuro?

and sfumato?

How deep?

Should it be rendered a paraclete of lost beauty,

a palimpsest, perhaps?

Consider this, he said,

it’s true; beneath the surface lies

another surface. But how many

must you uncover to find what you need?

I haven’t yet thought that far, I said,

but what about shape?

And size? One large with many small?

Amorphous? Perhaps it would be nice

to have them all angular,

sharply defined. The shapes

will have to get to know each.

Will they fight or make love?

He turned back into the wind. I could tell

by the movement of his ears he was smiling.

What about surface? I asked.

Texture. Should it be real or trompe l’oeil?

Should it dance with a scumble

or a stipple? How clear should it be? How muddy?

What of the sheen? Should light slide across

in a very slick fashion?

He bent to the earth

and scooped up a handful of dirt.

I suppose matte would do, he said, scrubbing out

an unwanted passage.

He turned to me, away from the wind.

Everything often dies on the borders, he said.

That’s where you find the mood.

The pleasure.

The affliction.

Do you want it cosmic and reverential?

A mysterious essence moving into the center of things?

Something absurdly abstract? Or a political,

social implication, scratched then smeared in blood-red?

Profane deprecation?

A blind gesture?

Death?

What about a simple landscape, I said, or a Chinese vase

filled with peonies?

There is always the portrait. Always that.

I remember well Dr. Gachet’s, his face filled

with what seemed wistful regret

beneath that ocher hat, his hands

painted a delicate flesh tint, a blue frock coat,

the yellow books on a red table,

the foxglove plant with purple flowers.

He looked up just as a crescendo of wind-

scattered clouds and a rabble of crows

sped across the burning fields, a flash of black

against the gold, against the blue and white sky.

Someday, he said, pointing at the billowing canvas,

someone will look at this

and find themselves amazed to know they were here

in this stand of ragged wheat,

with all these hungry birds diving into the shadows. You

with all your questions and me leaning into the wind.

This is where they’ll find us, in this painting;

this is where we’ve always been.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.