During the spring of 1967, on my way to lunch in the Student Union Building at University of Alaska in Fairbanks, I happened upon a recently published Popular Science magazine that featured a story about a new French invention. The article described a device that used infrasonic sound waves controlled in such a way as to emit varying degrees of intensity and, depending on the level, the weapon could cause vomiting, fainting, seizures, and even death. The scientists had discovered these ultra-low frequencies in the prevalent winds of southern France, known as the Mistrals.

I was particularly excited about stumbling across this article. As a student of painting and music, I had no interest in weapons, and, at the time, little interest in science but I was captivated with what I read. Like many young students of art, I was very much under the spell of the French Expressionist, Vincent Van Gogh. Perhaps it was the overall tragedy of his life ending so young. What other artist looms so large an archetype of a suffering, creative genius? I read everything I could get my hands on, including the letters he wrote, most of which were to his brother Theo, but to others as well. There were numerous letters to him and from others about him, particularly the French painter Paul Gauguin who briefly lived with Vincent in Arles, France.

I felt I had stumbled upon the clues to my own little Rosetta Stone. No one has ever been able to give a precise reason for Van Gogh’s journey into madness and ultimate suicide. It has often been suggested that he was epileptic. When he was clinically treated in 1889, two doctors diagnosed Vincent with epilepsy – seizures consisting of acute mania with sensory hallucinations, particularly affecting sight and hearing. However there is no indication that he suffered from epilepsy prior to his arrival in Arles. Still others have long argued that his daily intake of absinthe was essentially what drove him over the edge. Absinthe is a strong alcoholic drink made in part with a poisonous, hallucinogenic ingredient called wormwood. I tend to agree that the latter is the stronger candidate, but, in my opinion, it was a combination of everything – the absinthe, his upbringing, genetic imprints, and his environment, i.e. the winds.

In a letter to Theo, Vincent recounted that when he first arrived in Arles, as he was getting off the train, a man getting on the train advised him to return to wherever he came from because, quite simply, the people in Arles were a bit strange. This is not unusual and similar behavior has long been reported in other areas where extreme winds prevail over long periods of time, causing anxiety and depression among local residents.

It should be noted that Van Gogh did not cut off his entire ear. He merely sliced off a portion. Some say the helix, the upper part of the external ear and some say the lobule-what we call the ear lobe. In any case, doing so and sending it to a prostitute in a small box, as well as his general anti-social behavior in the small city of Arles, prompted the good citizens to lock him up in the insane asylum at nearby Saint Rémy. Sometime later, during his recovery, he asked permission to leave for the day to paint in the countryside. Earlier, during his time in Arles, it wasn’t unusual for him to spend hours each day struggling with ‘plein air’ painting, his easel staked to the ground and his canvases tied to the easel to prevent the mistrals from toppling everything over. In this case, as he was mostly recovered, the asylum allowed him a day pass. During this long afternoon of painting, the winds came up quite fiercely. It was reported that later that evening Van Gogh became terribly distraught and set about drinking his painting turpentine.

I rather doubt Vincent’s suicide can be attributable to any single event, yet I find irresistible the poetic imagery imbued in the possibility of the artist being dismantled by the winds. It isn’t a great leap of the imagination to see the mistrals appear in the paintings he painted while in Arles-the swirling energy found in the application of pigment as if he were as much hearing the un-hearable as anything he could see before him. Did he sense the destructive forces of the winds? I’m sure he did. What poignant irony that he tried to cut off the organ that helps sound enter the brain and shape our mental perceptions.

When Vincent was released from the asylum and left the south of France, he went to Auvers-sur-Oise, twenty-seven kilometers northwest of Paris and was somewhat under the care of Doctor Gachet. Within months after arriving, it is generally held that Vincent went to a small wooden shed, shot himself in the heart, collapsed, revived and returned to the Ravoux home in which he boarded. He died the following day. The daughter of Monsieur Ravoux, Adeline Ravoux, who was twelve yeas old at the time, wrote an account of the event some years later. However, buried in the original published letters, there is an account indicating that he shot himself in the groin. How can this be reconciled? One plausible explanation: The date, 1890, was during the final decade of the Victorian era. This was a period of such enormous prudishness that even pianos could not be said to have legs. Anything sexual or anything having to do with those parts of the body were immensely taboo. It’s more than likely, if Vincent’s wound had been in the groin, this would not have been discussed or divulged to the general public and certainly not to a twelve year-old girl. According to Vincent’s statement, as he lay dying, when he revived from shooting himself, he tried to find the gun to finish off the job, but could not. The gun was never found. In her accounting, Adeline suggested that Vincent did not commit suicide; that, in fact, he was murdered. By whom?

Even without medical knowledge, one could easily suppose that a man shot in the groin might survive longer than had he been shot in the heart. Obviously, had he intended the heart, he must have missed by some degree. If we assume that it was a wound in the groin, we can only wonder why there, whether self-inflicted or not. It took over thirty-seven hours for him to die in extreme pain.

There has long been a belief by many that Van Gogh was homosexual. While there is no evidence to prove this, there is no evidence to disprove it. We do know that he was enormously fascinated with fellow painter Paul Gauguin. In fact, after Gauguin left Arles, he wrote to a friend that on two occasions he woke in the middle of the night to find Vincent standing above his bed. When he asked what Vincent was doing, Vincent turned and fled out of Gauguin’s bedroom.

In her account, Adeline writes, “That Sunday he went out immediately after lunch, which was unusual. At dusk he had not returned, which surprised us very much, for he was extremely correct in his relationship with us, he always kept regular meal hours. We were then all sitting out on the cafe terrace, for on Sunday the hustle was more tiring than on weekdays. When we saw Vincent arrive night had fallen, it must have been about nine o’clock. Vincent walked bent, holding his stomach, again exaggerating his habit of holding one shoulder higher than the other. Mother asked him: ” M. Vincent, we were anxious, we are happy to see you to return; have you had a problem?”

He replied in a suffering voice: “No, but I have…” he did not finish, crossed the hall, took the staircase and climbed to his bedroom. I was witness to this scene. Vincent made on us such a strange impression that Father got up and went to the staircase to see if he could hear anything.

He thought he could hear groans, went up quickly and found Vincent on his bed, laid down in a crooked position, knees up to the chin, moaning loudly: ” What’s the matter, “said Father,” are you ill? Vincent then lifted his shirt and showed him a small wound in the region of the heart. Father cried: “Malheureaux,

[unhappy man] what have you done?”

“I have tried to kill myself,” replied Van Gogh.

These words are precise; our father retold them many times to my sister and I, because for our family the tragic death of Vincent Van Gogh has remained one of the most prominent events of our life. In his old age, Father became blind and gladly aired his memories, and the suicide of Vincent was the one that he told the most often and with great precision.”

Clearly the young girl saw Vincent come in, bent over, holding his stomach and in great pain, but she did not accompany her father to the bedroom and only relies on her father’s words as to the location of the bullet wound. Thus history has recorded it.

Here remains an untold and unsolvable mystery. Did he, in fact, take his own life or did someone murder him? We have no idea where he really went nor who Vincent might have seen and under what circumstances. As it stands in history, all of this – his neural highway shattered from infrasonic sound waves and his sexual coding – might mean little in the shadow of his monumental genius and what he left us. On the other hand, it does no harm to muse upon any mystery nor the possibility that Vincent ended his life because he could not find a way to express what is most fundamental in human nature-ones sexual identity.

Societies and their cultural skins have changed remarkably in some ways from the prurient age of Queen Victoria. The 20th century ushered in radical changes, such as nuclear weapons, television, fast food and the great sexual revolution I witnessed in the 1960s. Many of us believed that out of these winds of change a paradigm would rise; something more lasting with a greater understanding of the fabulous panoply of humanity and a deeper well of tolerance for racial differences, religious and non-religious beliefs, and sexual expressions. What came seems short lived.

In the last few months, a number of young people have committed suicide and many more suffer from brutal teasing and physical abuse. The sexual blueprint of these children is given to them by the grace of nature, yet many are choosing death rather than suffer unwarranted shame and the pain of our ignorance and intolerance. Are we doomed to devolve? Our cultural trajectory is never linear and seems weighted by anxiety, doubt and fear; history reveals how mythical are men’s wings.

Whenever the winds come up, I cannot but think of Vincent toiling in his solitude beneath the intense sun of Southern France, wondering what his paintings might have been like had he not gone south and wondering, too, what more immeasurable gifts he might have left us had he, himself, not left so young.

Panom, Galen

ANNOUNCEMENTS:

Look for the launch of a new collaborative project with writer and poet Peter Weltner coming in mid-January: A book-in-progress called ‘The One-Winged Body’ along with a newly designed web site.

Everyone here at baan Panom wishes all of you a gentle and joyful Holiday Season!

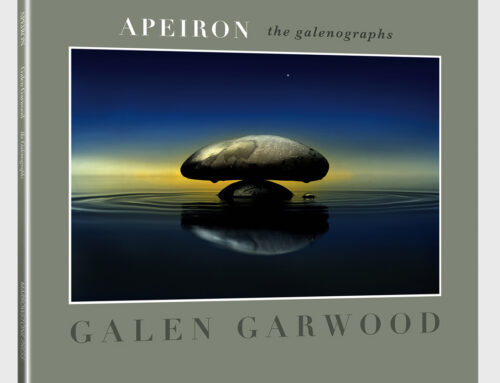

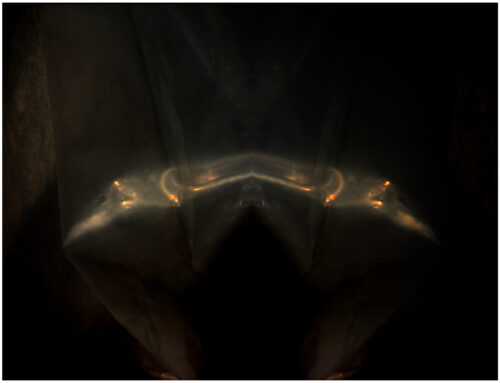

* the included images are monotypes I created on my large French/American etching press during the 1990s.